Some Bullshit Never Dies

Sometimes a lie collapses under its own weight, yet it doesn't change a thing.

Today’s article is kind of a long one, so your email might cut it off at some point. I recommend reading it on the site instead (just click the title).

So far in this series about lies, we’ve looked at how false narratives are born and the ways those narratives can take hold in the public discourse. In a sane or reasonable world, even if some bullshit does manage to get into the water supply, it shouldn’t be able to survive for long. A lie, no matter how well-packaged, is still a lie, so it would seem that flushing it out is just a matter of coming up with enough evidence to prove it’s a lie. Unfortunately, getting rid of a lie once it takes hold is rarely quite so simple.

Nobody likes admitting they’ve been duped. We tend to think of ourselves as reasonably intelligent people with at least a baseline understanding of what’s going on around us. We believe we are savvy enough to spot a lie when we see it and by the same token we believe that anyone who doesn’t spot the lie had it coming. Just look at the words we use to describe people who fall for bullshit: saps, chumps, dupes. Another word is “victim,” but we never use that term because we don’t regard these people as worthy of our sympathy. They are schmucks, rubes, more to blame for believing a lie than the liar is for having told it in the first place.

Since none of us is really as clever as we think we are, everyone falls for a lie at some point. But when it inevitably happens to us, do we change our opinion of those other people? Of course not. We turn into Principal Skinner. Was I taken in by some run-of-the-mill bullshit that I’m actually sort of embarrassed to even repeat because I know you’re going to look at me differently? No, I’m the target of the most sophisticated and complex scam ever perpetrated in human history.

Because the world we live in is neither sane nor remotely reasonable, very few lies die out on their own; fewer still die out because the people who believe them were presented with incontrovertible evidence. Most lies die out because the people who told the lies in the first place got what they wanted out of it, so they stop pushing those lies as much. (Those lies are never truly dead; if a lie works once, you better believe the liars will pull it back out the next time they need things to go their way.)

The reason so few lies die out on their own or in the face of proof to the contrary is because that’s just how we are as human beings Americans in particular). We will go to extreme lengths to avoid admitting we’ve been hoodwinked; the bigger and dumber the lie, the harder we’ll fight to save face. And as long as people choose to remain willfully ignorant of objective reality, even a lie that seemingly everyone knows is a lie will never truly go away. It clings to us, like the stench of sulfur clings to a drinking glass. Every now and then, it recirculates through the pipes, resurfacing just long enough to taint a fresh batch of marks. We’re stuck with it.

Remember Havana Syndrome? That mystery illness that causes a variety of inexplicable and embarrassingly mild neurological symptoms like headaches, vertigo, and difficulty concentrating and has been the bane of CIA spooks the world over? The one everyone initially insisted was proof that Cuba had developed an advanced microwave weapon, but then they changed it to “someone gave it to Cuba” because yeah man, that was why nobody was buying this whole thing? And they blamed Russia because even real life is just an exhausting series of reboots? And everybody got worked up about it that eventually our own State Department convened a panel of the nation’s top scientists to get to the bottom of things? Only the scientists’ conclusion was “Sounds like stress and crickets,” to which everyone in power replied Nope, brain gun did this?

(Am I already regretting my stylistic choice to recap everything in the form of a question? Yes. Do I feel like it’s too late to back away from it now? Also yes. Sorry.)

Remember how the president signed a bill ensuring that, on top of their already-great healthcare, CIA and State Department employees would get extra health care compliments of the U.S. government, even though their insurance already covers two-thirds of the medications you could use to treat Havana Syndrome (Adderall and Diazepam) and they can get Advil at a gas station? Remember all that? Well if you didn’t, you do now.

In January, the CIA sort of admitted the whole “Havana Syndrome” uproar was bullshit when they released a report acknowledging that most cases have environmental or medical causes. At the same time, they also insisted they were still investigating two dozen incidents, but we all know where this road ends. Eventually the CIA will quietly release another report saying most of the remaining two dozen cases were also not caused by an invisible brain ray, but we’re still looking at these 10. Then there will be another report (we’re still looking at these four), then another (okay, these two), then another (24th time’s a charm, right guys?), until enough time has passed that they can stop pretending to investigate a thing that doesn’t exist without getting laughed at for having taken it seriously in the first place. Even our institutions are desperate to save face.

Despite the CIA’s admission, in a January poll, only 4% of respondents said they believe Havana Syndrome is—pardon the pun—all in the victims’ heads. Meanwhile, a staggering 33% believe it is A) real, and B) caused by “directed microwave radiation,” “a sonic or acoustic weapon,” or “pesticides or some other infectious agent.” Another 9% said it was caused by “something else” (but if microwaves, sound guns and pesticides are off the table, it’s unclear what exactly that “something else” might be); 51% said they were “not sure.”

We already know it’s possible to weaponize sound, because we (of course) invented the technology; therefore, it stands to reason that if anyone was capable of developing this kind of weapon, it’d be us. There isn’t a weapon in the world that the U.S. doesn’t make or hasn’t already tried to make for itself, so the notion that we would be completely caught off-guard by any weapon doesn’t really make logical sense. Nevertheless, one-third of Americans still believe some foreign nation sank untold sums of money into developing a top-secret weapon that makes you…feel kinda funny(?); that they did so without us finding out about it (??); and then, uh, gave it to Cuba(???).

There is simply no way in hell it’s easier for someone to believe all that (and ignore the ever-growing pile of evidence to the contrary) than it is to say Huh, I guess Havana Syndrome isn’t real and just go on with their life. It can’t be.

So…what the hell? Why are we so hellbent on believing something we know is untrue?

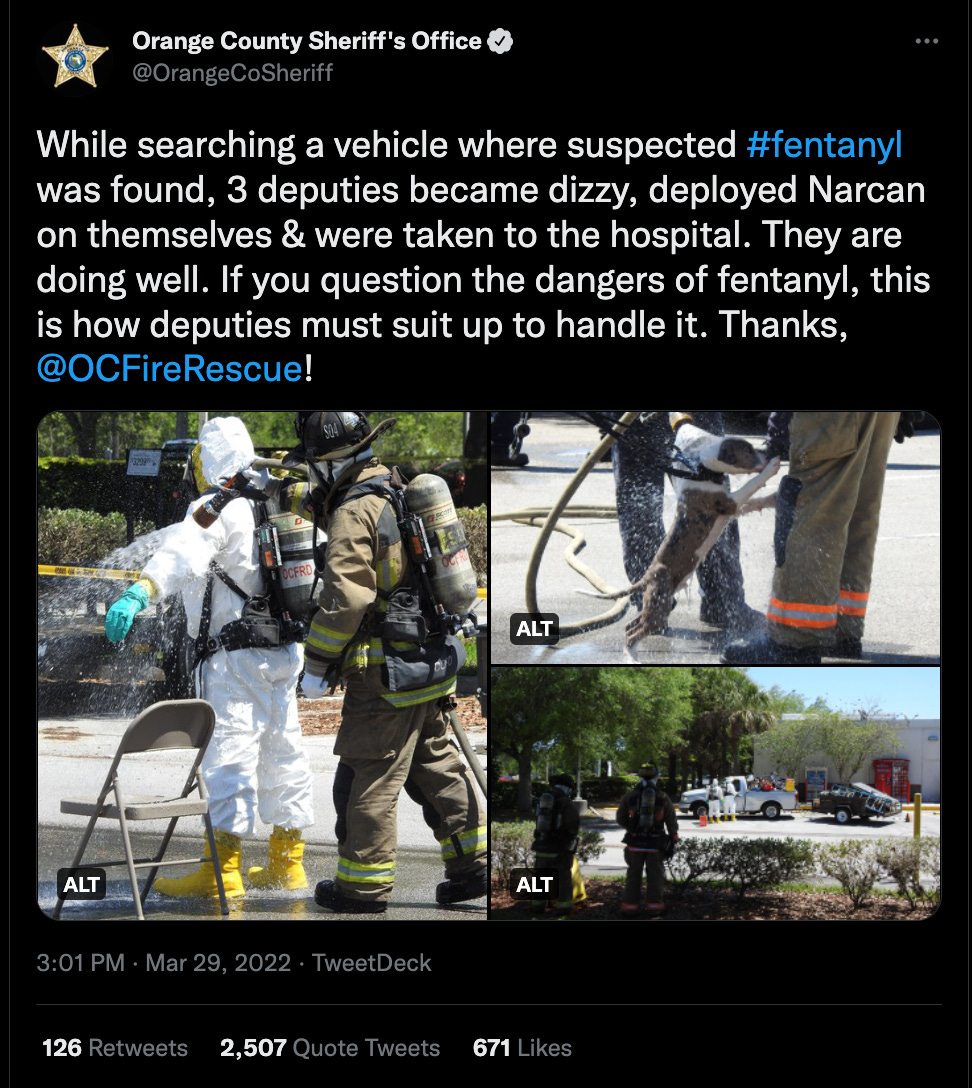

Every few months, some local Sheriff’s Department goes viral with a video of a cop thrashing on the ground captioned “This brave officer of law enforcement, in the course of enforcing the law as an officer, deployed his bare hands to enter into an engagement with fentanyl, which proceeded to cause an overdose and left him fighting for his life. This is the danger our men and women in blue have to deal with EVERY DAY!” The latest installment just dropped:

Hey, you know who wasn’t taken to the hospital? The person who was (allegedly) driving around in a cloud of fentanyl. Do you know why they weren’t? Because in order to overdose on fentanyl, you have to actually consume fentanyl. (Yes, there is a form of fentanyl that’s designed to be absorbed through the skin, but it differs slightly from fentanyl in powdered form, both in terms of how it’s consumed and because it looks like a patch that says “Fentanyl” right on it.)

Fentanyl is used in surgeries all the time, but surgeons aren’t dropping dead left and right. You don’t see anesthesiologists getting ready to administer fentanyl by putting on hazmat suits like they’re about to walk into the core of a nuclear reactor. Yet three cops stand kinda near a substance they think might be fentanyl, and suddenly everyone’s geared up like Dustin Hoffman in “Outbreak.”

Last year, the San Diego Sheriff’s Department shared a video purportedly showing a cop accidentally overdosing on fentanyl. After the officer collapses (in the slowest, most careful fashion imaginable), the other cop on the scene administers Narcan while shouting various Generic Cop Things like Hang on, brother! and You’re not dying today, dammit! Four doses of Narcan later, the cop is still unresponsive, and if you’re overdosing so badly that four doses of Narcan isn’t doing anything, then odds are extremely good that your breathing has stopped. But instead of starting CPR, the other officer just keeps rolling him on his side and…kinda gently rubbing his sternum(?) while hollering Stay with me! I’m too old for this shit! It’s my last day before retirement!

Eventually an ambulance shows up, but it doesn’t look like anyone administers CPR while they’re in the ambulance either, and when your breathing stops and nobody performs CPR, you generally—oh, what’s the word?—die. Since the officer is still alive and not severely brain-damaged, then it’s probably safe to assume he didn’t need CPR because he was breathing just fine on his own. Which means he didn’t overdose on fentanyl.

It’s not a fantastic sign that the people tasked with confronting the fentanyl crisis head-on have apparently learned so little about fentanyl that they don’t even know the symptoms of an overdose well enough to convincingly fake one. If they’d bothered to learn, say, anything about opioids in the past decade, they’d know that opioid overdoses don’t usually manifest as dizziness or fainting spells; the more common physiological effect is, ah…not breathing.

You know what causes fentanyl overdoses? Snorting or injecting fentanyl. You know what causes dizziness and fainting spells? Panic attacks. (Also lying.) You would think police departments would stop posting these obviously made-up and easily disproved horror stories after the first time they got called out for trying it, but they keep cranking them out anyway.

The charitable reading is that some cops are so freaked out by fentanyl that simply being in close proximity to any unidentified powder is enough to induce a full-blown panic attack; if that’s the case, though, it would seem that those cops are not psychologically equipped to withstand the stress of the job. The less charitable but probably more accurate reading is that cops are acutely aware of how fentanyl actually works and these big dramatic scenes are all for show, a farce intended to bolster the increasingly tenuous narrative that they have dangerous jobs. After all, it’s worked before: in 2017 a cop “overdosed” on fentanyl by brushing it off his uniform and it made national news.

It makes sense that cops would continue to keep trotting out this lie about fentanyl, because it behooves them to do so. The “policing is dangerous” narrative absolves cops of any manner of sins; any lie, no matter how brazen or unbelievable, is justified as long as it furthers that narrative. If all it takes for cops to hold onto their get-out-of-jail-free card is a few wasted doses of Narcan—which doesn’t have any effect on someone who’s not overdosing, by the way—and tying up an EMT crew for an hour or two, of course they’re going to do it.

Obviously the cops shouldn’t be lying about fentanyl in the first place, but expecting cops not to lie to make themselves look good is a fool’s errand. It’s what they do. What I can’t understand is why anyone who’s not a cop would choose to believe them. (And plenty of people do, as evidenced by the comments on both of those posts.) The average citizen doesn’t seem to get anything out of the deal, so why participate in this charade at all?

The police only have as much power as we allow them to have. Cops are 2.5 times more likely to kill a black man than a white man, even though black people who have been shot and killed by cops are twice as likely as white people to be unarmed. But since cops are rarely—if ever—punished for their actions, they have come to believe that their actions are warranted and that they have our tacit permission to do the things they do.

Police often think of themselves as the physical manifestation of negative consequences; thus, an action or a behavior is not inherently bad until they get involved. For example, a fistfight is a neutral event—unless someone calls the cops about it. Only then does that fistfight become the codifiable Bad Action of assault. Taking this logic to its natural endpoint, nothing a cop does is bad; if it was, someone would call the cops on him.

The best way to understand how much power cops have is to identify the point at which their actions begin to have negative consequences. Everything up to that point is fair game. The cops have the power to carry out extrajudicial executions of certain people; they have the power to steal certain people’s property, sell it, and keep the profits; they have the power to abuse and demean certain people. The cops derive that power from everyone who sits above those “certain people” in the social hierarchy, and we’ve all seen how cops behave towards those certain people over whom they have power. Perpetuating the lie that cops have dangerous jobs invariably leads to cops being granted more power over more people—including, eventually, the people who helped grant them that power in the first place. So why would those people help the cops by carrying water for them?

Because they want it to be true. They want it to be true so badly, in fact, that they will do everything they can to try and make it true, even if doing so is ultimately to their own detriment.

The interesting thing about lies is that if enough people believe them, they can eventually become true without ever becoming more factually accurate. Liars need their lie to be “true”—i.e., believed—in order to achieve whatever it is that prompted them to concoct the lie in the first place; as Harry G. Frankfurt writes in his essay “On Bullshit”:

Telling a lie is an act with a sharp focus. It is designed to insert a particular falsehood at a specific point in a set or system of beliefs, in order to avoid the consequences of having that point occupied by the truth.

Imagine I go into a bank and hand the teller a note that says I have a bomb strapped to my chest and I’ll blow the whole place to kingdom come if I don’t get all their money. I don’t actually have a bomb, but that’s beside the point: I just need the people in the bank to believe I do in order to get the money. I can’t get what I want unless they believe my lie; thus, I need it to be true.

The telltale signs of a bomb (a detonator, something bulky hidden under my coat, wires sticking out higgledy-piggledy because I wouldn’t know how to build a bomb anyway, etc.) are conspicuously absent; all the evidence suggests that I do not, in fact, have a bomb. Most bank tellers who notice this would tell me to fuck off, because no matter how badly I need them to believe it, my lie is still a lie. But some tellers would hand over the money anyway, because what if I do have a bomb? How can they be sure I don’t? They’re not experts on bombs; maybe I’ve invented a new, tiny bomb and they just can’t see it. Maybe they’d give me the money because they already believe the world is full of thieves and criminals, and now they have a story to support their worldview. Whatever their reasoning, they choose to ignore the hard evidence in front of them and believe my lie instead. They want it to be true.

People choose to believe policing is as dangerous as cops say it is and that cops are the only thing standing between them and a total breakdown of societal order. The cops need this lie to be true in order to amass more power, which allows them to continue operating unchecked; their defenders want it to be true because they believe they are better than those people, or because they don’t like the people who think cops are bad, or because they don’t want to grapple with the question of whether policing as an institution does more harm than good. They are not the victims of the status quo (and they assume they never will be), so they are satisfied with the status quo.

The CIA and the government need us to believe Havana Syndrome is real so they can get permission to colonize Cuba or go to war with Russia or some other thing that they’ll probably end up doing anyway. And people choose to believe them because they still believe in the idea of America as a superior nation, a shining city on a hill. They want it to be true because thanks to a steady diet of red scare nonsense since the 1950s, many of us have developed a reflexive dislike or distrust of foreign countries (especially communist nations), and if this is true then their xenophobia is justified. They want it to be true because if the CIA and the government are lying about this, what else will they lie about? And what else have they already lied about?

The Wall Street Journal and the retinue of ghouls populating the paper’s op-ed section need us to believe that capitalism is the only viable political and economic system available to us because their livelihoods depend on it: their job is to help the rich continue profiting off of everyone else’s labor without us ever getting wise to it. And people want to believe that anyone can get rich as long as they work for it because if wealth is only preordained for the wealthy and down to luck for the rest of us, then why are we grinding ourselves to the bone to turn a profit for someone else?

The reason some lies never seem to die is because, for whatever reason, we keep them going. When we do, each of those individual lies becomes hopelessly entangled with the rest, and each new lie just adds to the knot. As a consequence, our reality is comprised of countless individual lies that, for a multitude of reasons, have gone unchallenged, and for many people, that raveled and matted mess becomes all they know.

I don’t know what the solution is. I don’t even know if there is one. It’s frustrating that people cling to bullshit, but can you really blame them? It’s a lot easier to believe something that jibes with everything that you already know all the way down to your bones is true about the world than it is to tear down your reality and start a new one. If your world is just a knot of bullshit anyway, what’s the harm in adding one more little lie to the pile?

It’d be a lot easier to tolerate bullshit if it only affected the people who fall for it, but that’s not how it works. We may not share the same reality, but we’re all still bound by the connective tissue of our shared humanity, so inevitably their knot of bullshit intrudes upon our lives. And once that knot is brought in, it becomes a part of our world. It doesn’t matter nothing about that knot is factually accurate, because it exists nonetheless and therefore comprises part of what is for the rest of us.

Maybe if we were more comfortable admitting when we’ve been duped, the knot wouldn’t have gotten as big as it has. We might never get rid of the whole knot, but there’s no time like the present to start pulling on some threads.