Let It Fall

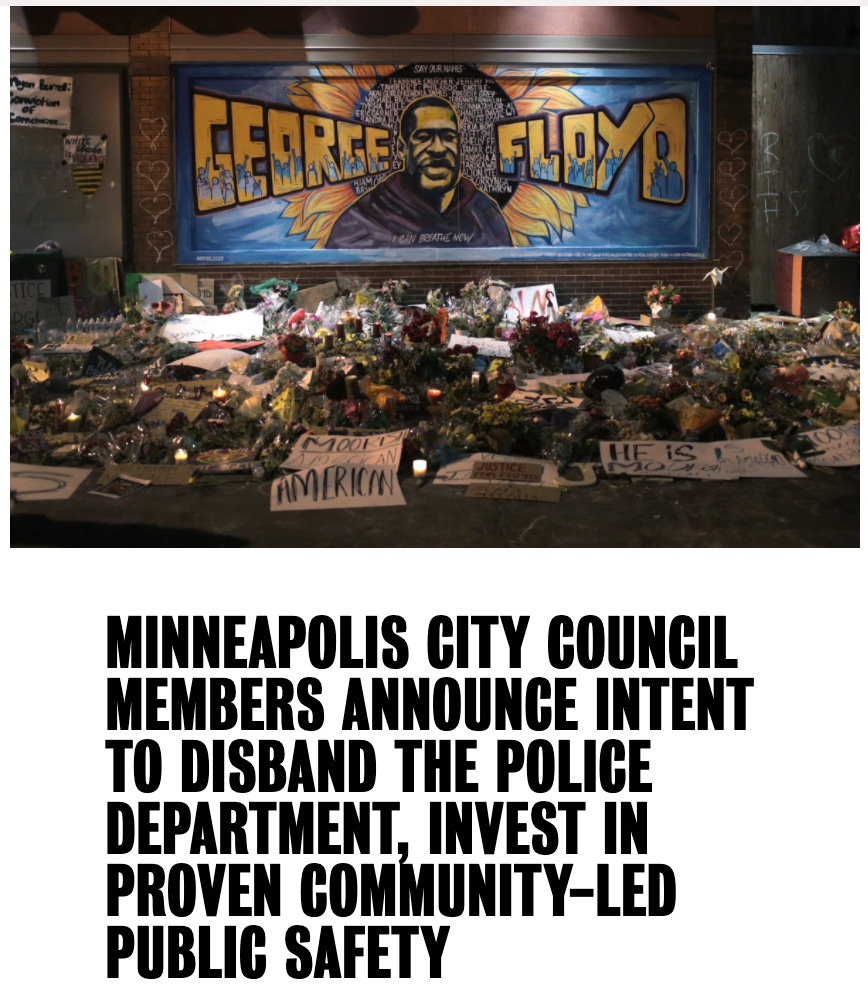

On May 25th, George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis.

Floyd was arrested by Minneapolis police officers for allegedly attempting to pass a counterfeit $20 bill at a convenience store; in the course of the arrest, Officer Derek Chauvin pinned Floyd to the ground with a knee to the neck.

Over the next 8 minutes and 46 seconds, Floyd told Chauvin and the three other officers that he couldn’t breathe. He called out for his mother. He begged for his life. Eventually, he stopped saying anything. Even after Floyd fell silent, Chauvin’s knee remained on his neck for another 2 minutes and 53 seconds.

I don’t know that there’s anything to be gained from analyzing the sequence of events that culminated in the murder of George Floyd. There are really only two reasons why anyone would do so: either to identify all the things Chauvin could have done differently, or to evaluate Floyd’s actions in an attempt to find something that would justify his murder. In either case, any insights resulting from such analysis would be meaningless because they rely on the fundamentally erroneous belief that what happened to George Floyd was an aberration.

There is nothing remarkable about Chauvin’s behavior or actions. The three other officers blithely take in the scene, indifferent to the fact that a man’s life is slowly being taken right before their very eyes. They are not concerned because there is no cause for concern; this is business as usual. They are unperturbed when Floyd becomes unresponsive after being choked for 5 minutes and 53 seconds; this, too, is what is supposed to happen. They are not alarmed as Floyd is choked for nearly three more minutes. The only time their demeanor suggests something is amiss is when they realize that Floyd is dead. Everything that took place before that moment unfolded exactly how they expected it to. Exactly how they wanted it to.

There is no identifying where it all went wrong, because up to the instant the police realized they’d killed him, everything had gone right. There can be no pinpointing the moment where, had things unfolded differently, George Floyd would still be alive today. That moment came when it was already too late, which is to say it never came at all. Like Eric Garner, George Floyd was never going to survive the treatment the police decided he deserved. He never stood a chance. And that’s the point.

Following Floyd’s death, there have been renewed cries for sweeping police reform. I doubt any such reform will actually occur. But even if it does, the larger question remains: is reform even possible? How do you remove violence from policing when policing requires the threat or use of violence to survive? What tweaks are there to be made to a system that views the murders of George Floyd and Freddie Gray as necessary sacrifices to the status quo? How do you fix that which does not believe itself to be broken?

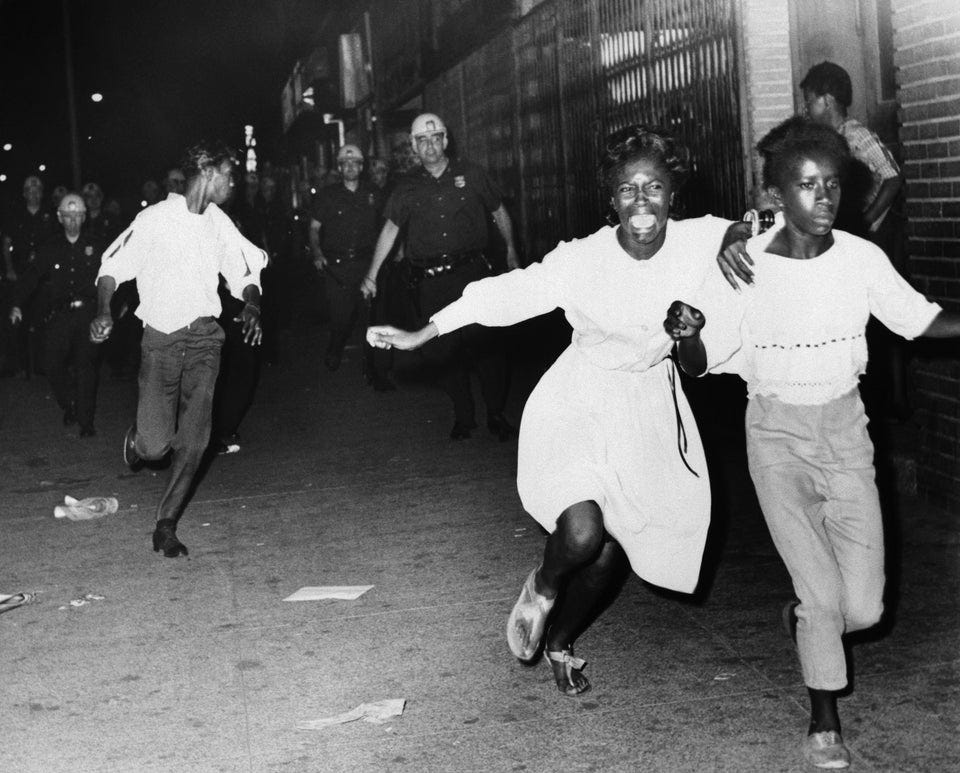

This picture was taken during the Harlem riot of 1964, a six-day riot that began when Lt. Thomas Gilligan shot and killed 15-year-old James Powell in Harlem, in full view of Powell’s friends and a French class at a nearby school. (The image was later used as the album cover for The Roots’ 1999 album Things Fall Apart.) It’s a powerful photo. Partly because I live about a 15-minute walk away from where that picture was taken on Fulton Street in Bed-Stuy; my grandmother and great-aunt grew up just a few blocks away. But the scene depicted would still be haunting even without my physical and familial connection to it.

Start with the girls in the foreground. The girl in the white dress is terrified of what might happen if the cops catch up to them. Her outfit—white dress, sandals, no hair out of place—suggests she didn’t plan on running from the police. Her friend, on the other hand, is dressed in pants and a blouse with closed-toed shoes, almost as if she expected to run. She’s stone-faced, focused, like she already knows what happens because she’s witnessed it firsthand, and she’s hell-bent on making sure the same fate doesn’t befall her. Behind them is a young man in full stride, peering over his shoulder as though Death itself is in pursuit, because on that night, it is.

A boy stands in the doorway. He’s young, possibly young enough that if he were white, he’d still probably believe that the police are always the good guys. But black kids learn the truth a lot earlier in life than white kids do. He looks like he wants to step out of the doorway and see what’s going on, but he knows better. He’s curious, as all children are, but his instinct for self-preservation overrides his curiosity. Such an instinct should not exist in someone so young.

The cops bring up the rear. Their uniforms almost blend into the darkness, lending a spectral, disembodied quality to their white helmets and white faces. Their billy clubs are already out, cords wrapped around their wrists. They are not there to restore order to the community; they’re there to inflict pain on anyone who stands in their way. If the riots quiet down as a result of the beatings they dole out, fine; if they don’t, well, the beatings will continue until they do. They are grinning. Smirking.

There’s an old black folk song called “Run, Nigger, Run.” In the antebellum South, slaves weren’t allowed off the plantation without a pass from their owner, but some slaves would sneak away without a pass to visit friends at other plantations nearby. The song was a warning to anyone who decided to leave the plantation without permission: if the slave catchers (often called “patty-rollers”) are on your trail, don’t stop—run.

In the movie 12 Years A Slave, one of the white characters taunts the slaves with the song, forcing them to sing along with him.

That same malevolent glee is evident on the cops’ faces in that picture—they’re enjoying every minute of this. Their expressions are almost triumphant; they know there’s nothing stopping them from beating those children to death if they want to. Run, run, NYPD’ll catch you/Run, nigger, run, oh you better get away.

Now look at Chauvin’s expression.

It reminds me of a poacher posing triumphantly over the corpse of an endangered species. He wears an imperious expression, almost daring the person behind the camera to do something about what they’re witnessing. It’s the look of someone who believes they have the right to do whatever they want to whomever they please. He almost seems exasperated by the crowd’s reaction to what he’s doing. Their anger is an affront to his authority.

None of his attention is on George Floyd, pinned under his knee and struggling to stay alive. Why would it be? The conquest of Floyd is complete; Chauvin has imposed his will, and all is right in his world. George Floyd isn’t a suspect anymore, he’s a trophy, a warning to everyone else that the penalty for defiance in the face of absolute authority is death. Run, nigger, run, the MPD’ll catch you/If you don’t run, well I’ll kill you anyway.

“Peace, quiet, and good order will be maintained in our city to the best of our ability. Riots, melees, and disturbances of the peace are against the interest of all our people, and therefore cannot be permitted.”

-Mayor Benjamin “Ben” West in 1961, during one of the first sit-ins at a segregated lunch counter in Nashville, TN.

“Tearin’ shit up with fire, shooters, looters: now I got a laptop computer”

-O’Shea “Ice Cube” Jackson in 1992 on “We Had To Tear This Mothafucka Up,” released after the Rodney King verdict and subsequent riots in Los Angeles, CA.

The first protest took place the next day in Minneapolis. Soon, there were protests in 400 towns in every state in the country, then in 25 countries across the globe. Before long things turned violent, because of course they did. What other outcome can there be, when aggressive cops with a free pass to commit violence are handed supervisory authority over a protest precipitated by aggressive cops committing violence? What did anyone expect?

The overwhelming majority of police officers believe they are a tribe unto themselves, separate and distinct from the rest of society. They are the “thin blue line” standing astride chaos and order: better than the scumbags they apprehend, nobler than the ordinary citizens who couldn’t last a second on the job. You need them on that wall. They don’t view themselves as part of society but as something outside of it, an omnipotent entity floating slightly above the fray.

It’s as much a coping mechanism as anything else. Imagine you saw someone shooting heroin and you—and only you—had the power to force them to spend the next four years in a tiny room, plus ruin the rest of their life after they got out of that room. Could you do it? Could you live with knowing not only that you took away the life they could have had, but that you chose to do it? I doubt you could; most people can’t. So how do cops do it? Simple: they try to remove humanity from the equation. When their badge is on, they’re not people; they’re merely instruments of the system. It is the system’s decision to ruin that person’s life, not theirs. They cannot control it any more than a river can slow its current to prevent someone from drowning.

For most people, the goal is to not be noticed by the police; the more they notice you, the greater your odds of being sucked away in their current. Surviving an interaction with the police is a lot like surviving a mugging: whatever you do, don’t push back. If a cop wants to berate you for running a red light, let them do it. If they want to push you around a little bit, let them do it. If they start beating you, don’t fight back. The penalty for disrupting their fantasy of unquestioned dominance is often death. George Floyd paid that penalty. So did Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, Walter Scott, Alton Sterling, Laquan McDonald, and God knows how many others.

Time and again, the police respond violently, telling us it’s because “the faster we get things under control, the safer everybody will be.” But it’s not about safety, and it never has been. It’s about intimidation, putting the fear of God into anyone foolish enough to question their authority. Police violence is in itself a demonstration, a protest against your right to protest; an organized effort to make you too fearful to organize. Their job as they see it is to keep people in line, and they’re more than willing to use brutality to make that happen. They rely on your instinct for self-preservation to outweigh your anger.

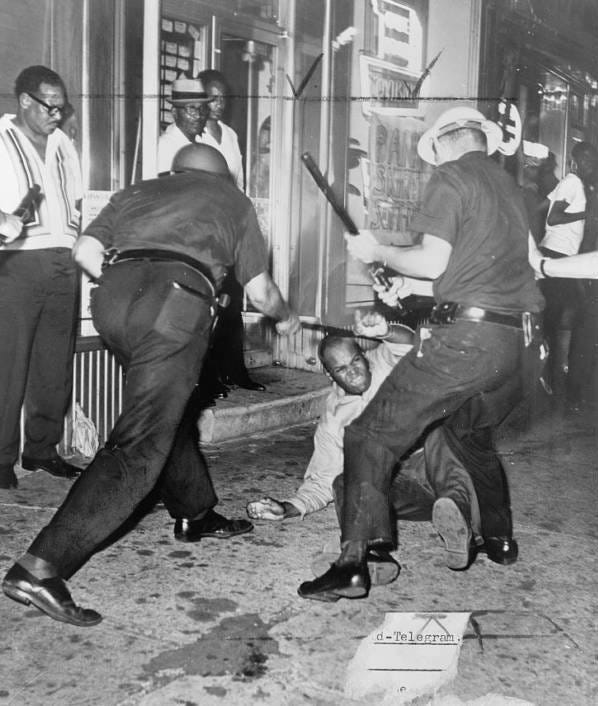

Black Americans have been asking for change for decades, only to be told “No” in so many different ways. Not right now, but once we win this election…Sometimes the answer comes in the form of a police baton:

Or from a dog:

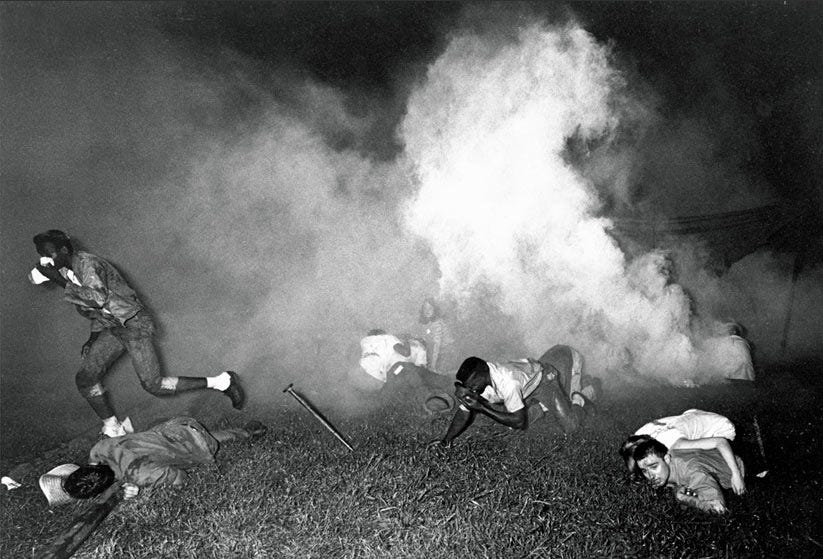

Or with tear gas:

Or under the guise of “more humane” crowd control.

No matter how it comes, the answer is always “No.” But there’s something different about the protests this time. The protesters aren’t just angry, they’re nihilistic. They’ve spent their lives watching as the meager concessions the state granted their parents and grandparents are systematically dismantled under a new generation of hatred and bigotry. They’ve been told there’s a “right” way to go about effecting change, one that just so happens not to disturb or discomfit those in a position to make that change happen. They work longer hours at jobs that may or may not exist tomorrow, doing their best to maximize profits for a company that won’t even pay for their health insurance, all to earn a paycheck that doesn’t go as far as it used to. If they point out the injustice that has been baked into our society, all they get is sympathetic clucking and empty promises from feckless politicians.

Somehow, despite all that, they keep making the best of it. But on May 25th, they watched a video of George Floyd being choked to death for eight minutes and 46 seconds and they were reminded that the system isn’t content to withhold from them the life they deserve—it wants to take the life they have. And they decided to fight back the only way they can: with a good old-fashioned riot.

Riots are, by nature, unfocused, a collective expression of outrage that is less about striking back than it is about striking at all. Protests are about advancing a specific political or social ideal; in a riot, finding a solution to a problem is secondary to just doing something. What we saw in Minneapolis was different: it had the explosive energy of a riot, but there was a clarity of purpose.

The police responded with savagery and brutality, because that is what the police do. But the violence did nothing to restore order, because the crowd watched George Floyd get murdered and saw police in riot gear lining up in formation, and realized that whether it happened that night, the next night, the next month, the next year, the next decade, the violence is coming. No sense delaying the inevitable. The next night, the crowd responded by setting fire to the Third Precinct where George Floyd’s murderer worked. It was a message not just to the Minneapolis PD, but to the country:

We don’t need the police.

The police maintain their grip on power through physical force, but there is a mental component at play as well. Whenever citizens complain about astronomical police spending or a small-town department supplying its officers with military gear thanks to a DoD discount, the police suggest ominously that they’re the only thing standing between us and some unspeakable horror.

For many protesters, the police themselves are the horror—the will of a racist and inherently unequal system made manifest. If the police have nigh-limitless power and minimal accountability in order to more effectively protect us, and they not only fail to do so but actively harm us, why do we continue to grant them this power?

In the immortal words of Anton Chigurh: “If the rule you followed brought you to this…

…of what use was the rule?”

These videos—and 400 more just like them, all taken since the protests for George Floyd started—make clear that the police don’t value your community, your safety, or your life. Policing is about power: preserving power in order to wield it, wielding power in order to preserve it. The same police officers who kneel in ‘solidarity’ with protesters have been caught, over and over again, brutalizing those same protesters an hour or two later. We are told that police officers who are punished for murdering unarmed black men and women (or, more accurately, for being caught doing it) are “a few bad apples.” They are, but the saying isn’t “A few bad apples are acceptable, so don’t worry about it”; it’s “A few bad apples spoil the whole barrel.”

Derek Chauvin murdering George Floyd, the Buffalo cop in full riot gear who nearly killed a 75-year-old white man for blocking his path, the NYPD officer who pulled down a peaceful black protester’s mask so he could pepper-spray him more: all reminders of the pervasive rot of policing. The three officers who watched Chauvin murder Floyd and did nothing, the NYPD Union that defends the actions of cops who go out of their way to harm innocent people, the 57 officers who resigned from the Buffalo PD in solidarity—with the cop who was suspended: incontrovertible proof that policing is both beyond salvation and not worth saving anyway.

The peaceful protests, the sit-ins, the petitions, the calls to reform policing as though policing as it exists today could ever be meaningfully reformed: those were the carrot. The police refused to accept the carrot, because they demand nothing less than absolute dominion over the communities they are meant to protect.

So now they’re getting the stick.

No justice, no peace.